Imagine a scenario where one of the most widely-revered animators of all time disliked animating and grew bored of the job relatively early in their career. It’s a surprising idea, and frankly a little hard to believe. We tend to assume that success comes from love for the craft, and when someone excels at their job, it’s because they’re fueled by creative passion.

That wasn’t always the case though for Ward Kimball, whose life I’m chronicling in If It Ain’t Fun, To Hell With It! Ward Kimball’s Adventures in Disney, Jazz, Trains, and the Avant-Garde. The upcoming book is a comprehensive cradle-to-grave biography about his life and creative process, drawing on exclusive access to previously-unavailable materials, including his personal journals.

A central theme in the upcoming biography is Ward’s creative restlessness, and his refusal to be boxed in by animation, Disney, or anyone’s expectations. While artists often devote a lifetime to perfecting a single craft, Ward was ready to move on once he had mastered his, always drawn to explore new modes of expression. It’s a side of him that has largely been overlooked in previous accounts of his life.

The basic version of Ward that most people know is that he was Disney’s wildest animator — and that’s an indisputable fact. He was the Disney animator who bent the studio’s films to his will, and in doing so, expanded the boundaries of the Disney animation style. But this tidy narrative doesn’t capture the full breadth of his accomplishments, nor does it represent how he actually felt during the time he animated.

About a decade into his career, Ward began feeling discontent as an animator, and by the fifteen-year mark, he was eager to leave animation behind completely. His distaste for animating was no secret at the studio. Years later, after Ward had moved away from animation and his boss Walt Disney wanted to punish him, Disney reassigned him to the one job that he knew would demoralize Ward the most: animator.

Even though Ward excelled at the work of making characters come to life one drawing at a time, he was temperamentally ill-suited to the craft. By the late 1940s, he was often fatigued at work and found it difficult to focus on his animation. During this time, he began channeling his creative energy into music, and soon he had established a promising second career as bandleader and trombonist of the nationally popular jazz group The Firehouse Five Plus Two.

Ward wasn’t built like animation colleagues Frank Thomas or Milt Kahl, the kind of artists who could sit at their desk for eight hours a day with a colored pencil, content to animate a few seconds of daily footage. “I could never understand how Frank [Thomas] could be so patient, sitting there for 40 years doing the same thing with that little red pencil,” Ward once said. In another interview, he put it even more bluntly: “[I]f I had to sit there grinding out that damned footage, I’d put a pistol to my head.”

Further compounding his misery, he disliked many of the films on which he animated and felt that they were conceptually underdeveloped. “For many years, I criticized the directors for not being able to sense when a story point was right, or wrong,” he said. “I wanted to make decisions myself. If you were a working animator, you were at the mercy of poor decisions as far as directors were concerned, even though you did your utmost to rectify this when you animated a sequence.”

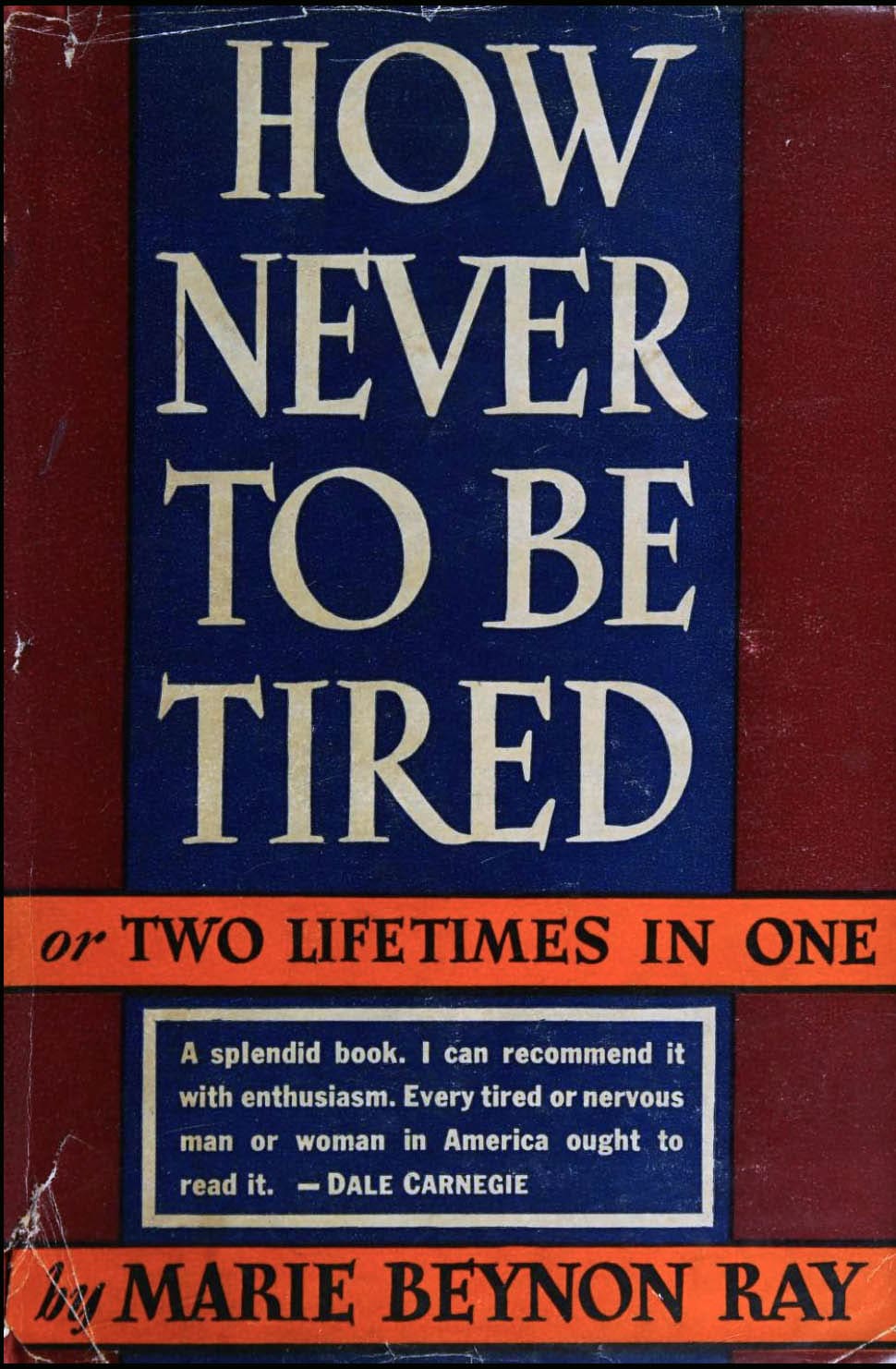

It was at this low point in his career that Ward stumbled upon a book that transformed his life. The book was Marie Beynon Ray’s How Never To Be Tired, originally published in 1938 under the title Two Lifetimes in One. The popular self-help book offered an intriguing explanation for Ward’s chronic weariness: fatigue isn’t caused by overwork but rather by boredom and being stuck in a job that a person doesn’t want to do. Fatigue, Ray argued, is primarily a psychological issue and to tap into our endless energy reserves, we have to find work about which we are passionate.

“Being tired is being bored,” Ward said of the book’s lessons. “And I was tired. I was animating, and it was easy, and it was effortless. I had to hypo myself by throwing myself in different moods.”

For someone who was innately interested as much in the film’s overall idea as their role in the film, he resolved to gain more control over the creative process by becoming a director. The story of how he became a director will be told in the book, but ultimately, his move into directing (as well as writing and producing) in the early 1950s marked the happiest and most creatively fulfilling period of his time at the studio.

Incidentally, Ward wasn’t the only Hollywood iconoclast who found inspiration from Beynon Ray’s book. Genius comedy director and writer Preston Sturges cited his discovery of the book as a life-changing event. A 1946 Life magazine profile of Sturges claimed that he never even read the book past chapter three, because those first three chapters sufficiently shifted his mindset. After reading the book, Sturges expanded his base of activities to include launching a restaurant and nightclub on Sunset Blvd., designing a yacht, and inventing various cinematographic devices.

One unexpected benefit of being a biographer is that, in committing to tell someone else’s story, we often end up discovering something about ourselves. In recent years, Ward’s discontent as an animator struck a personal chord, as I came to recognize parallels between his struggles at the studio and my own experience of running Cartoon Brew. We’d both been in our roles for roughly a decade and a half when we hit a wall. Like Ward, I was good at masking my restlessness and performing the work that was required, but over time, my desire to do the job and capacity to produce both diminished significantly.

Even when I wanted to write, I was spread too thin by the daily demands of running Cartoon Brew as its publisher. The more successful the site became and the more money it brought in, the more I grew to dislike the job.

In many ways, I’ve always been an accidental businessman. I never set out to run a widely-read industry news resource for the animation community, and while I was quite capable of doing the job, that hardly mattered. As a creative person, I couldn’t shake the feeling that every step forward for the company pulled me further away from my own passions and interests. I tried to make things interesting for myself (which in turn kept the site interesting for everyone else), but ultimately, the stifling constraints of running a trade publication outweighed any sense of satisfaction or accomplishment that came with the job.

The answer was always in front of me. As Beynon Ray explains in her book, the obligation to do a job that isn’t creatively fulfilling or mentally challenging is a boring job that one shouldn’t be doing. This doesn’t mean that running Cartoon Brew is inherently boring; in fact, it’s quite the opposite. But for me, the work gradually shifted from a dream job into an ever-tightening noose.

And while my path forward isn’t as clear-cut as Ward’s transition into directing, at least for the moment I’m back to writing about what I want and working on projects that feel meaningful to me.

That just about wraps up the first entry of this journal, but there’s plenty more to come. You can, of course, expect fascinating material about Ward, including a generous smattering of rarities gathered during my research. I hope it sparks your interest to pick up the book itself. It’s been a passion project years in the making and one that will be surprising to any fan of Disney or animation and inspiring to anyone in search of a creative boost.

But I want to be clear: this will be more than just a journal about the book. This is also a personal outlet, a space for me to write about whatever’s rattling around in my head. Many of the topics will undoubtedly revolve around animation, but the conversation will also branch into other territories. The common thread tying everything together is that it’s stuff I genuinely want to write about. After years of writing out of obligation, it feels like a minor miracle to have regained the ability to examine and discuss things that truly matter to me.

As a sidenote, I’m committed to keeping the writing on AmidAmidi.com (and accompanying newsletter) gratis forever; in this modern era of unlimited media, the time you spend reading and engaging with these pieces is more appreciated than any monetary value I could assign to the words.

Thank you for accompanying me on this journey into a new and uncharted era of my life. While I can’t guarantee that everything I write will be enthralling, it will be a candid and unfiltered reflection of where I am and what I’m thinking. I’m glad you’re here.